13 Hampden Road

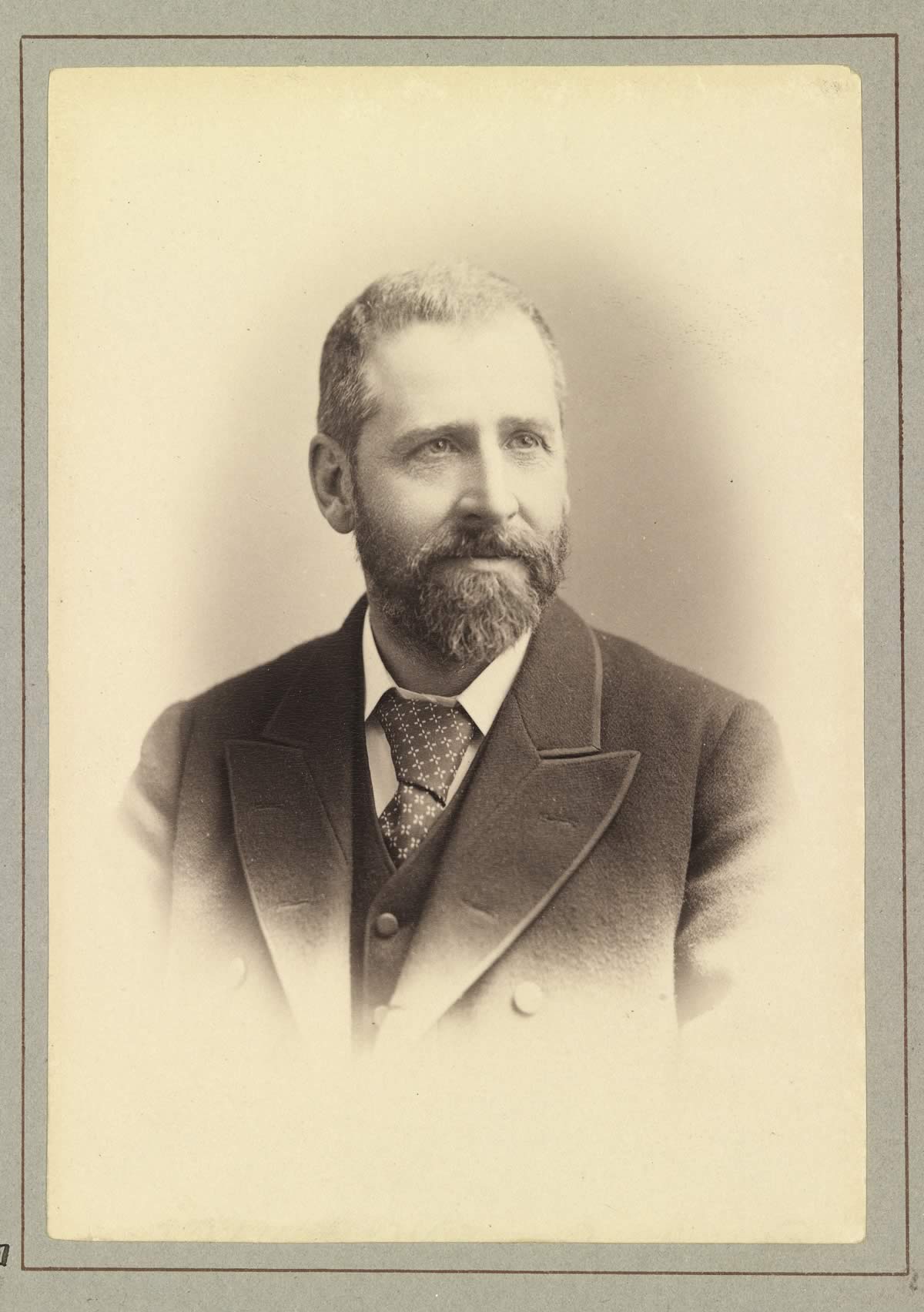

Rosebank was built by Andrew Inglis Clark, a significant figure in Australian public life. Clark was elected to the Tasmanian House of Assembly in 1878 at a time when Australia was moving towards nationhood. Attacked by the Hobart Mercury as a revolutionary with his ‘proper place among the Communists’, Clark was a staunch republican and believed that government should benefit everyone.

He supported progressive legislation including legalising trade unions, reforming laws on lunacy, employment, custody of children and prevention of cruelty to animals. He advocated women’s suffrage and contributed to the development of the Australian Constitution. He is largely remembered today for the Tasmanian Hare Clark system of proportional representation in political elections.

Clark was a criminal lawyer but his refusal to accept anything beyond a modest fee prevented him from making a fortune. He was appointed Judge of the Supreme Court and played a major role in the foundation of the University of Tasmania in 1889, later serving as Vice-Chancellor from 1901 to 1903. In private life, Clark made plenty of time for his family. His son Conway remembered him under his ‘vine and figtree’ with his wife and children at Rosebank.

Clark was lucky that his father had an engineering business and could afford to give his children a good education. Despite his wealthy background, Clark always supported the underdog and wrote:

The leopard could as soon change his spots as I become a supporter of plutocracy and class privilege.

Andrew Inglis Clark died in 1907.

… The leopard could as soon change his spots as I become a supporter of plutocracy and class privilege.

Listen

Generous by nature, and broadminded to a degree, [Andrew Inglis Clarke] was a passionate advocate for the true democracy which means the affording of equal opportunities to all men… Only a few days before his death, he told the writer what a terrible strain upon his mind had been a trial before him, in which wealth had been matched against widowhood and poverty. ‘I am too soft to be on the bench!’ He said, and in that sentence summed up the stress which, in the end, helped to shorten his life. …

In politics, he remained true to the liberal principles which had inspired him from the first. Fearless in his utterances on all public questions, and careless of consequences when he had once struck out upon the course which he believed to be right, he won for himself a character for rectitude which anyone might well envy.

– Alfred J Taylor, Daily Telegraph Launceston, Thursday, 21 November 1907

Andrew Inglis Clark

Source

Tasmanian Archive and Heritage Office AUTAS001136192051

Andrew Inglis Clark’s home Rosebank before Clark’s modifications

Source

University of Tasmania Library Special and Rare Materials Collection

Andrew Inglis Clark’s home Rosebank after Clark’s modifications

Source

University of Tasmania Library Special and Rare Materials Collection

Rosebank 2015

Photo

Private collection

Rosebank by Victor 2015

Source

Albuera Street Primary School

Rosebank by Harley 2015

Source

Albuera Street Primary School

Corner of Hampden Road and Colville Street from Secheron Road c1943

Without the kindness of shopkeepers, especially one on the corner of South Street and Hampden Road, Mum would never have managed… He would put out what he thought were the necessary groceries and put them on the doorstep.

– Bill Foster talking about his childhood in the 1930s

Source

Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery Q6082.24

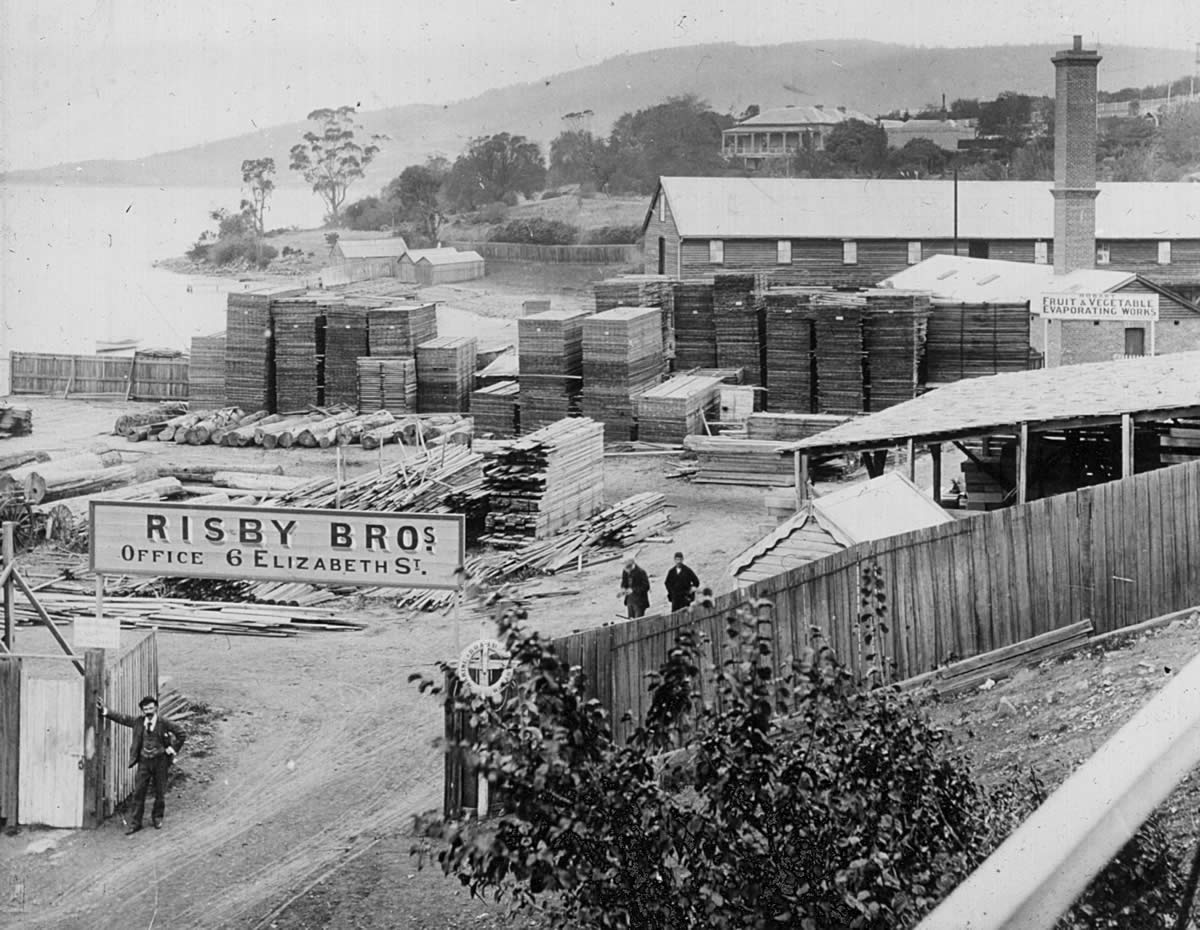

The original wharf on Battery Point was built for Risby Bros timber yard c1920s

Huon Cry fruit processing factory later occupied the same site. Secheron House is in the background.

Source

Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery Q2001.15.8.61

Huon Cry fruit processing factory in the foreground 1940s

Rosebank just out of shot at top of photo. The industrial–residential mix of Battery Point has long gone.

Source

Tasmanian Archive and Heritage Office PH 30 1 8993

Huon Cry liquid fruit during WWII 1940s

Many of the local Battery Point women worked in the fruit factory.

Source

Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery Q2413

Processing fruit at Huon Cry 1940s

Source

Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery Q2411

Processing fruit at Huon Cry 1940s

Source

Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery Q2412

Dispatch room at Huon Cry 1940s

Source

Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery Q2410